Summary

- Emerging research shows that the gut microbiome is a key player in the development and progression of breast cancer.

- Factors that negatively impact the microbiome are diet, obesity, and antibiotic usage.

- Dysbiosis (dysfunctional microbiome) contributes to breast cancer by weakening the immune system, impacting critical hormone balance, and rendering cancer-fighting phytochemicals ineffective.

- In this two-part series, we will define the problem and suggest evidence-based solutions to resolving dysbiosis-related issues.

Breast cancer is the second most common cancer in women in the US, and 1 in 8 women will be diagnosed with the disease during their lifetime (1). We know that certain factors like genetics and obesity can increase the risk of disease development, but over 50% of breast cancer cases are unrelated to known risk factors (2). Clearly, much work needs to be done to fully identify the underlying risk factors related to the disease.

Emerging research supports a new risk factor for the development of breast cancer—dysfunction of the gut microbiome. The gut microbiome is the population of trillions of microbes that live in our gastrointestinal (GI) tract, and a dysfunctional microbiome is called “dysbiosis.” Is it possible that the microbiome is the missing link to our understanding of breast cancer?

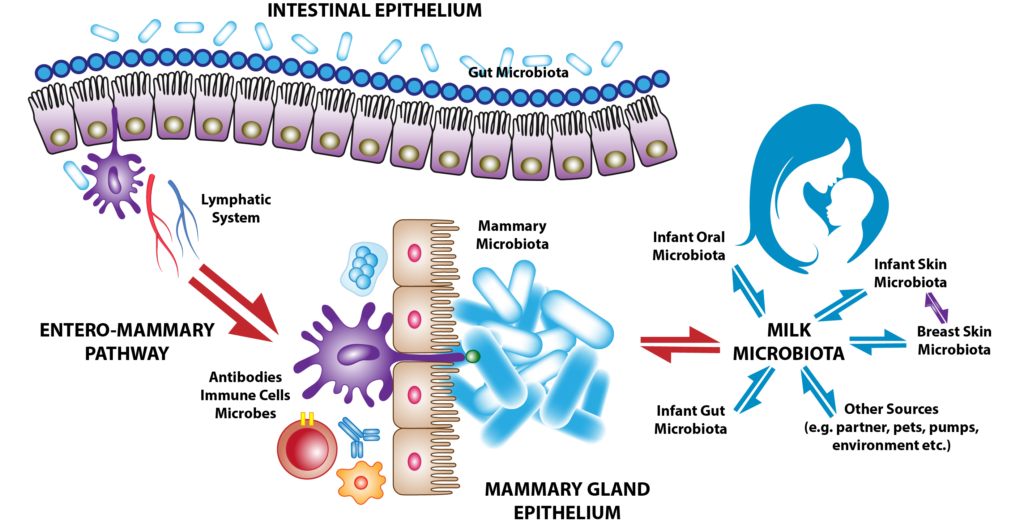

Your initial thought may be to question how the gut and the breast could possibly be connected. Let us start at the beginning: consider the fact that human milk is full of healthy microbes that originate from the mother’s gut; this is termed the “entero-mammary path,” and it describes the movement of the mother’s gut bacteria through the breast and into the infant’s GI tract (Figure 1) (3).

Figure 1. The entero-mammary pathway is hypothesized to carry immune cells, antibodies, and microbes through the lymphatic system to breast tissue. The microbes populate the breast tissue to create their own unique microbiome, which is essential to sustain breast health and impart immunity to the newborn child (3).

But the gut is not only connected to the breast microbiome; it also appears to directly impact several factors we know to be related to breast cancer, including estrogen and progesterone levels, the biotransformation of phytochemicals into anti-cancer substances, and immunomodulation. In the following sections, we’ll explore the impact of the microbiome on breast cancer. After setting the stage and establishing the link, part 2 of this blog series will discuss research-backed strategies for using your microbiome as both a shield and sword against breast cancer.

Microbiome 101

When you think of the microbiome, you may only think of bacteria. But in fact, the microbiome includes everything from bacteria, fungi, viruses, and parasites. In a healthy microbiome, most of these organisms are symbiotic, meaning both the human and the organism benefit and live together in harmony. However, many factors can disrupt this harmony, such as a poor diet, antibiotics, stress, or certain illnesses. Once disrupted, dysbiosis occurs, and disease can arise.

In recent years, we’ve started to see the importance of the gut microbiome and its role in everything from chronic disease to mental health. There is also growing scientific evidence that the alteration of a healthy microbiome plays a role in the development of several cancers. The study of the relationship between the microbiome and cancer even has its own word: the “oncobiome.”

But the gut is not the only part of the body that has a microbiome; the skin, mouth, and respiratory tract are just a few of the many areas with a unique microbiome. Indeed, there are few, if any, parts of your body that are completely sterile and free from microorganisms—and we need it that way! Healthy breast tissue even has its own microbiome—a relatively new discovery that occurred just within the last decade (4). In the years since, researchers have started analyzing the breast microbiome, and they’ve made some interesting revelations:

- Geography and ethnicity influence the breast microbiome. Individuals who live in certain regions have similar microbiome compositions (5).

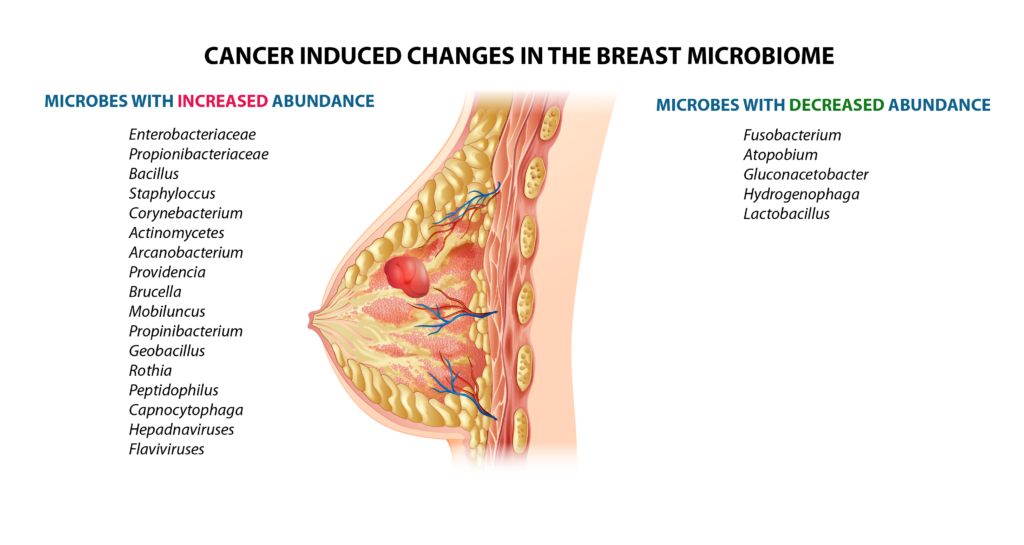

- There is a distinct difference in the breast microbiome between those with breast cancer and those without (Figure 2) (4).

- The breast microbiome changes depending on the stage of breast cancer (6).

Upon closer analysis of the composition of the breast microbiome, it appears that as cancer develops, “good” bacteria decrease, and “bad” bacteria increase (7). These changes are so pronounced it may be possible one day to look at the breast microbiome as a biomarker for cancer diagnosis! We may even be able to see if the microbiome is trending away from a cancer-favorable environment, which may help us stop cancer in its tracks.

Figure 2. Changes that convert the breast microbiome into an “oncobiome” (4).

It’s currently unclear if the altered microbiome causes the cancer or the cancer causes the altered microbiome. But if we take a step back, the holistic, integrative perspective shows us that when we look at the body as a whole, in most scenarios of disease development, the “cause” and the “effect” are often interchangeable. The good thing is that a healthy microbiome comes as a result of other healthy lifestyle choices. Together, all of these healthy decisions combine to decrease the risk of cancer and create a healthier you!

Regulation of Estrogen and Progesterone Levels

If breast cancer has ever touched your life or the life of your loved one, you may be aware that estrogen and progesterone are related to its development. Estrogen and progesterone are sex hormones dominantly present in females and, to a much smaller extent, in males. The estrogen and progesterone receptors in cells mediate biochemical pathways that can lead to the development, growth, and invasive behavior of breast cancer cells. That is why, even though they are endogenous hormones with important physiological functions, traditional medicine considers them to be carcinogens. From an integrative perspective, we prefer not to label our endogenous hormones as “carcinogens,” but instead stress the need to restore balance in the endocrine system.

Many normal life events cause fluctuations in hormonal levels that may increase or decrease the risk of breast cancer. For example, women who have not experienced childbirth, have early onset of puberty, or late onset of menopause are known to be at a higher risk of breast cancer. Also, exogenous hormones taken as medication have been connected with a higher risk of breast cancer.

Here’s the interesting part. Do you know what one of the major regulators of estrogen and progesterone is? That’s right—the gut microbiome! (8) This is a critical point because it directly links the microbiome to risk factors for breast cancer. Simply put, a diverse, healthy microbiome reabsorbs sex hormones like estrogen and progesterone; this decreases the exposure to sex hormones, thus decreasing breast cancer risk. On the other hand, dysbiosis leads to increased secretion of sex hormones, subsequently increasing cancer risk (9).

Biotransformation of Phytochemicals

The next point is related to phytochemicals or plant-based compounds obtained through our diets. Some of these compounds work with the microbiome to elicit beneficial anti-cancer effects. But research shows that in the absence of a healthy, diverse microbiome, they cannot elicit those powerful effects! For example, there is a group of phytochemicals called lignans that decrease breast cancer risk by their ability to modulate the levels of sex hormones in the body (10). Studies show that dysbiosis decreases the effectiveness of these breast cancer-fighting compounds by reducing their biotransformation in the gut (11).

Glucosinolates are another group of phytochemicals that are dependent on the microbiome. These compounds prevent cancer through their ability to induce apoptosis (cell death) and prevent angiogenesis (tumor blood vessel formation). But in order for glucosinolates to exert these positive effects, the body must first convert them to another group of compounds called isothiocyanates. Studies have shown that this conversion is dependent on a healthy gut; without a healthy gut, these compounds can’t exert their anti-cancer effects (12).

In the next article, we’ll further explore these breast cancer-preventative phytochemicals, where to find them, and how to incorporate them into your diet.

Immunomodulation

The next factor affected by dysbiosis is the immune system. Most people associate the location of the immune system with the lymph nodes or the bone marrow. But can you believe that 70% of your immune system is actually located in your gut? Your gut contains the most lymphoid tissue in the entire body and houses large numbers of immune cells and antibodies. The functional health of these immune cells is largely controlled by the gut microbiome.

The microbiome and the immune system are interconnected from the moment of birth. In the womb, babies (and their guts) are completely sterile. But during the baby’s birth, they pass through the birth canal, which coats them in bacteria and becomes their first microbiome. Also, as we saw earlier in Figure 1, the breast milk and colostrum-derived microbiome continuously replenish the baby’s microbiome until it is capable of sustaining itself (4, 6). As the baby grows, the microbiome teaches the immune system the difference between the body’s own tissues and foreign invaders, and it also teaches it which bacteria are good and bad. Throughout life, the microbiome continues to regulate the immune system and plays a vital role in defending the body against invaders.

Since the immune system and microbiome are so interconnected, it makes sense why dysbiosis can have such a negative impact on the immune system. Studies show that dysbiosis leads to an imbalance of 2 types of white blood cells—a decrease in lymphocytes and an increase in neutrophils (13). This is bad news for breast cancer patients because this precise white blood cell imbalance is shown to reduce survival.

Tying it All Together

Breast cancer and the microbiome are directly connected. A healthy microbiome can balance estrogen and progesterone levels, utilize anti-cancer plant compounds, and support a healthy immune system. When the microbiome becomes unhealthy, from factors like poor eating habits or antibiotic usage, it can contribute to the development of breast cancer and other chronic diseases. Fortunately, dysbiosis is reversible! In part two of this blog article, we’ll discuss research-backed strategies to improve the health of your microbiome and use it to fight breast cancer.

References

1. Key Statistics for Breast Cancer. (2023). https://www.cancer.org/cancer/breast-cancer/about/how-common-is-breast-cancer.html

2. Madigan, M.P., et al., Proportion of breast cancer cases in the United States explained by well-established risk factors. J Natl Cancer Inst, 1995. 87(22): p. 1681-5.

3. Rodriguez, J.M., The origin of human milk bacteria: is there a bacterial entero-mammary pathway during late pregnancy and lactation? Adv Nutr, 2014. 5(6): p. 779-84.

4. Eslami, S.Z., et al., Microbiome and Breast Cancer: New Role for an Ancient Population. Front Oncol, 2020. 10: p. 120.

5. Parida, S. and D. Sharma, The power of small changes: Comprehensive analyses of microbial dysbiosis in breast cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer, 2019. 1871(2): p. 392-405.

6. Bard, J.M., et al., Relationship Between Intestinal Microbiota and Clinical Characteristics of Patients with Early Stage Breast Cancer. FASEB Journal, 2015. 29(S1).

7. Urbaniak, C., et al., Microbiota of human breast tissue. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2014. 80(10): p. 3007-14.

8. Bodai, B.I. and T.E. Nakata, Breast Cancer: Lifestyle, the Human Gut Microbiota/Microbiome, and Survivorship. Perm J, 2020. 24.

9. Plottel, C.S. and M.J. Blaser, Microbiome and malignancy. Cell Host Microbe, 2011. 10(4): p. 324-35.

10. Pietinen, P., et al., Serum enterolactone and risk of breast cancer: a case-control study in eastern Finland. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 2001. 10(4): p. 339-44.

11. Knekt, P., et al., Does antibacterial treatment for urinary tract infection contribute to the risk of breast cancer? Br J Cancer, 2000. 82(5): p. 1107-10.

12. Shapiro, T.A., et al., Human metabolism and excretion of cancer chemoprotective glucosinolates and isothiocyanates of cruciferous vegetables. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 1998. 7(12): p. 1091-100.

13. Chace, D., Turning Off Breast Cancer: A Personalized Approach to Nutrition and Detoxification in Prevention and Healing. 2015.

Do you recommend taking the anti estrogen drug like Exestemene or Anastrozole if reoccurring breast cancer ER/PR

We are not able to give medical advice directly through our website or social media platforms. Please contact our admissions office at 888-544-5993 or go to https://hope4cancer.com/schedule-a-call/ and fill out the form so one of our admissions officers can get you a free consultation with our doctor.